Sleeping Venus

Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (1510; ill. 1) is a landmark: for the first time in Italian art, natural nudity and the beauty of the body become the true subject of the painting. Giorgione set the template for the “reclining Venus” that European art would repeat for centuries.

Of course, prototypes for this composition were already known from engravings of sleeping nymphs that go back to antique sculpture—such as the Sleeping Ariadne (2nd century BCE; ill. 2). And medieval European art had precedents for the nude (Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, 1486; ill. 3). But in those works nudity was not the sole, primary subject: Venus is shown standing, usually shielding herself with an antique drapery—the body held at the distance of myth. In Giorgione, Venus appears without the medieval fear of the naked body, stripped of symbolism and mythology.

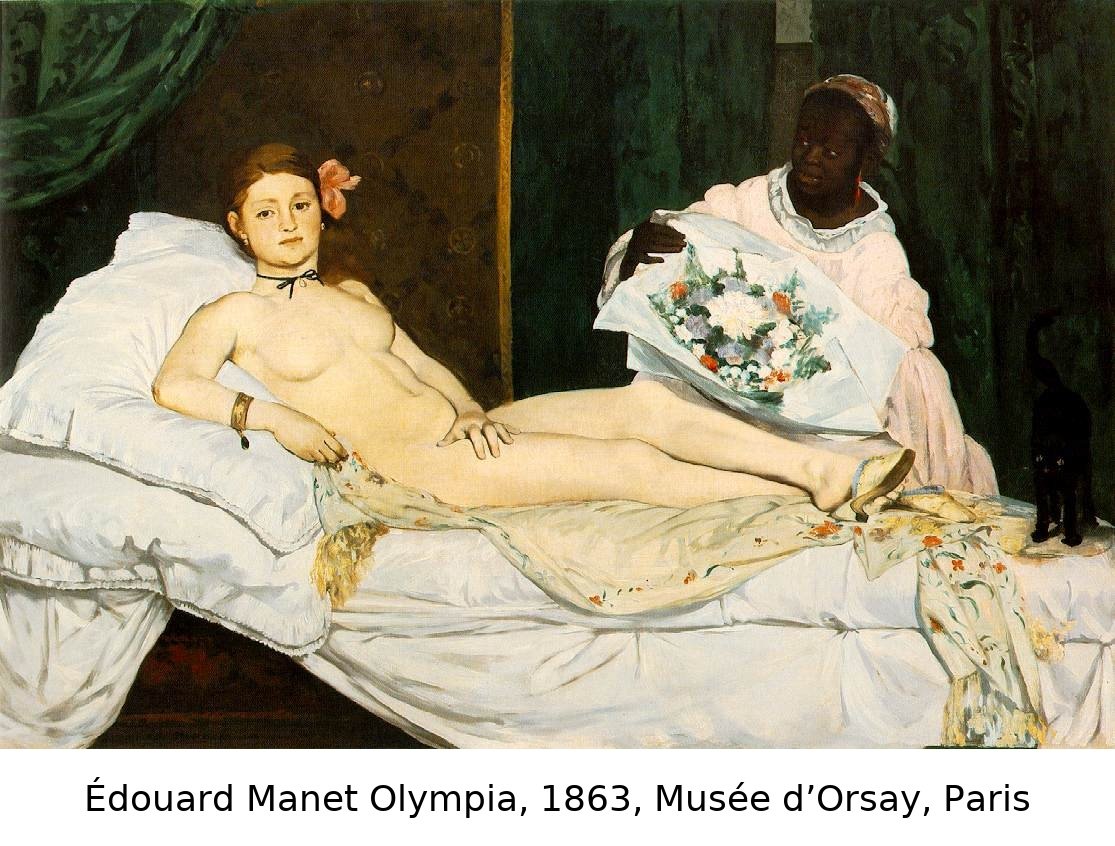

This composition and motif became canonical, the basis for countless future citations and reprises. Titian—who finished Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus after his death—perfected the device in his Venus of Urbino (ill. 4). Yet where Giorgione’s Venus is a goddess—chaste and harmonious, natural in her nudity (we have caught her unawares; she does not know she’s being seen)—Titian’s Venus is a courtesan (she knows she is watched and meets our gaze). Her steady look provokes, while the maids in the background and the little dog at her feet bring the scene down to earth.

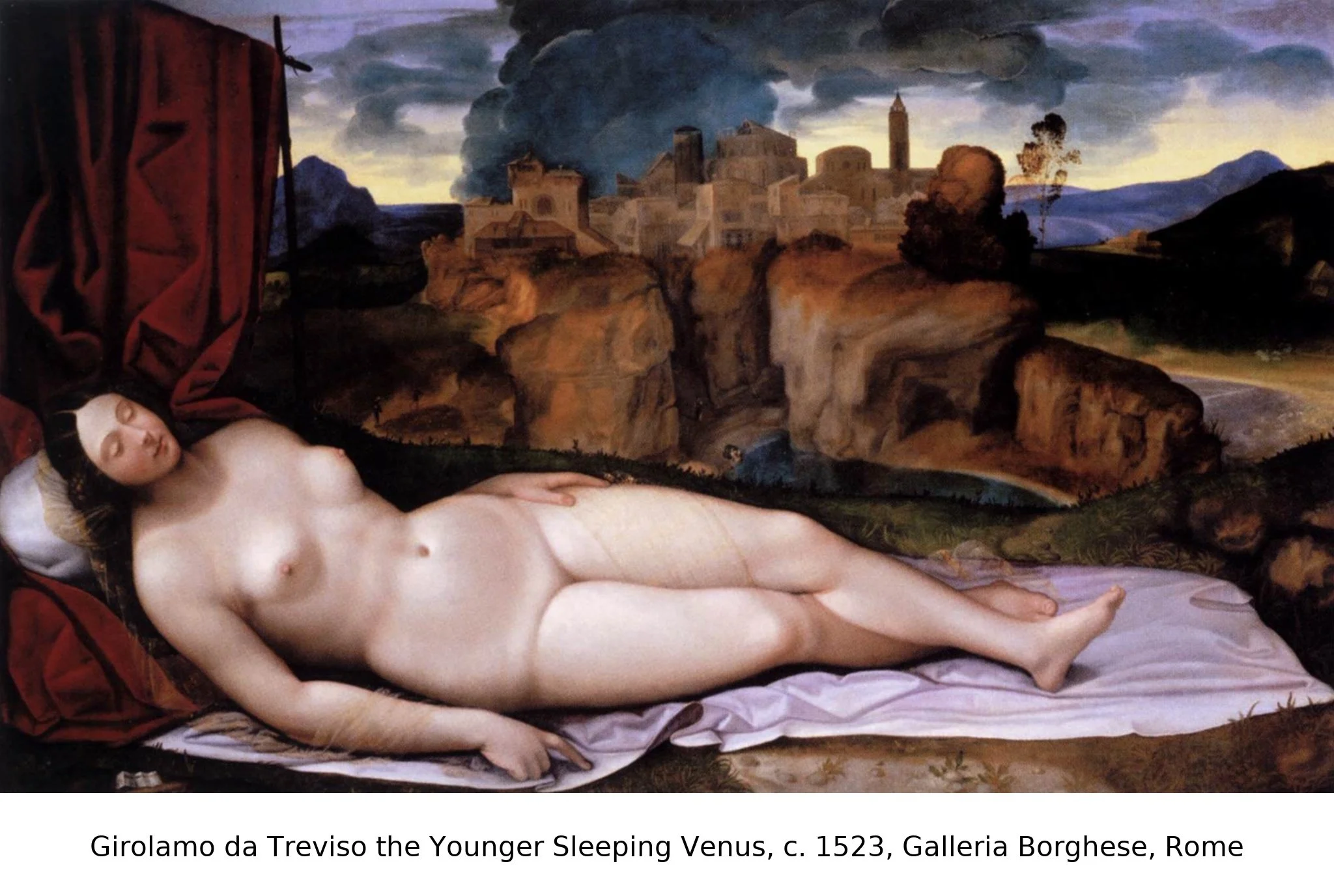

The long afterlife of this composition runs through Girolamo (Sleeping Venus, 1523; ill. 5), Artemisia Gentileschi (Venus and Cupid, 1630; ill. 6), Diego Velázquez (Rokeby Venus, 1644; ill. 7), Francisco Goya (The Nude Maja, 1800; ill. 8), Alexandre Cabanel (The Birth of Venus, 1863; ill. 9), Édouard Manet (Olympia, 1863; ill. 10), and others.