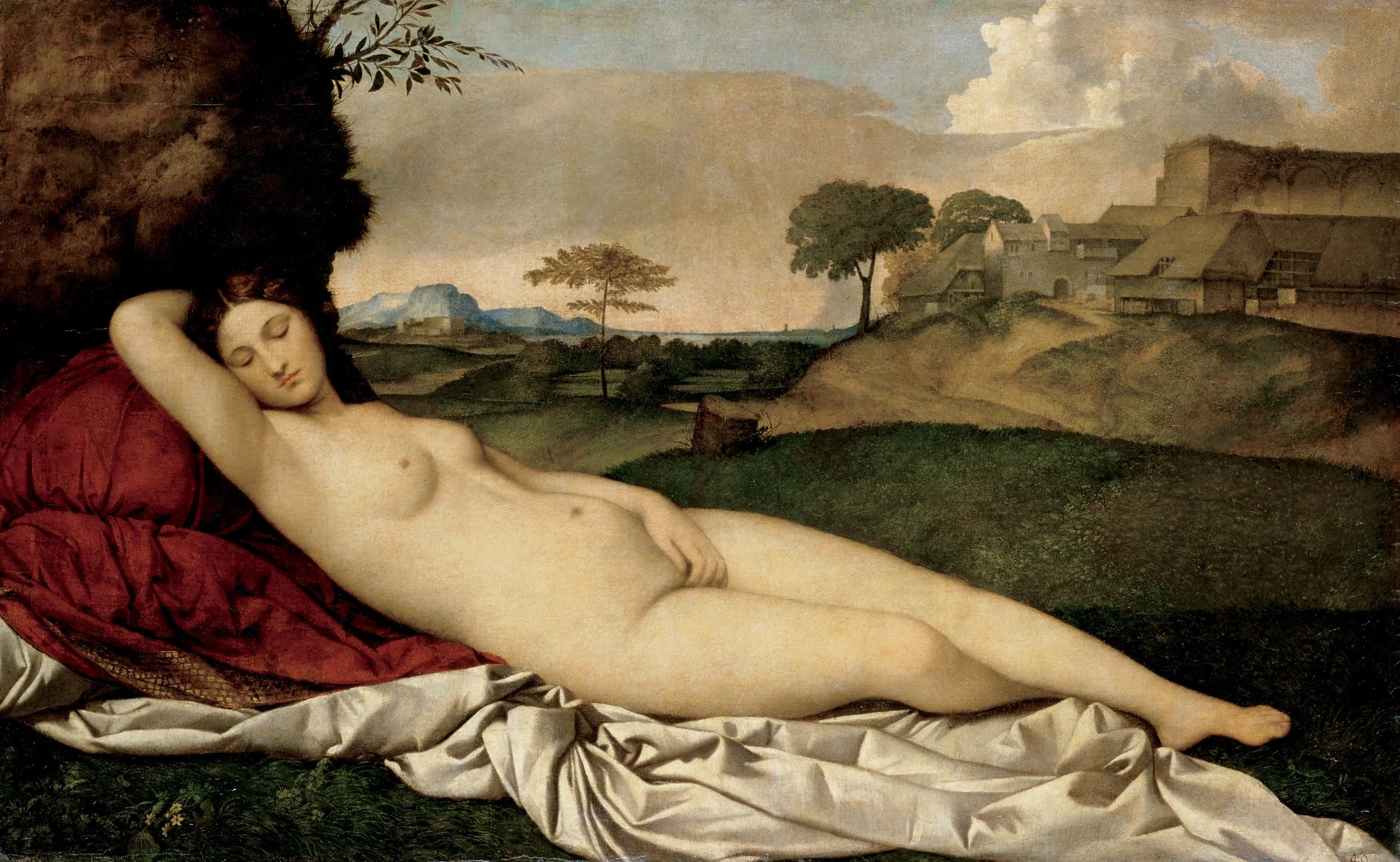

Sleeping Venus

Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (1510; ill. 1) is a landmark: for the first time in Italian art, natural nudity and the beauty of the body become the true subject of the painting. Giorgione set the template for the “reclining Venus” that European art would repeat for centuries.

Of course, prototypes for this composition were already known from engravings of sleeping nymphs that go back to antique sculpture—such as the Sleeping Ariadne (2nd century BCE; ill. 2). And medieval European art had precedents for the nude (Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, 1486; ill. 3). But in those works nudity was not the sole, primary subject: Venus is shown standing, usually shielding herself with an antique drapery—the body held at the distance of myth. In Giorgione, Venus appears without the medieval fear of the naked body, stripped of symbolism and mythology.

This composition and motif became canonical, the basis for countless future citations and reprises. Titian—who finished Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus after his death—perfected the device in his Venus of Urbino (ill. 4). Yet where Giorgione’s Venus is a goddess—chaste and harmonious, natural in her nudity (we have caught her unawares; she does not know she’s being seen)—Titian’s Venus is a courtesan (she knows she is watched and meets our gaze). Her steady look provokes, while the maids in the background and the little dog at her feet bring the scene down to earth.

Eirene and Ploutos

This statue once stood on a market square. The Athenians set it up to mark their peace with Sparta in the 370s BCE and the newly instituted state cult of Eirene.

Its chief interest is that Kephisodotos, the sculptor, introduced a new concept for a statuary group.

Eirene with Ploutos is the first prototype of a pairing that later European art would repeat in countless variants — the Madonna and Child.

The way Eirene inclines her head toward the child, and the way he tenderly reaches for her face, point to a new idea of constructing a group on an inner spiritual bond, a dialogue of feeling.

Later, along this same new path of lyrical, intimate motifs — previously unknown to Greek sculpture — went Kephisodotos’s probable son, Praxiteles. Less than half a century later he refined the approach in his Hermes with the Infant Dionysus.

The Uncleaned Floor

n antiquity there was a popular mosaic genre that imitates a dirty floor. These mosaics usually decorated banquet halls.

In the leftover scraps you can easily make out fruit, olives, assorted pits, chicken drumsticks, shells, claws, and fish tails and heads. On this mosaic there is even a mouse that has hurried over for a walnut.

What is striking is that the objects are modeled in volume and cast shadows. That tells us these mosaics spread in a period when artists had already mastered light-and-shade modeling, roughly the fourth to third centuries BCE.

As a rule, the “uncleaned floor” ran as a border or outer band of a larger composition and complemented the main scene. This particular example (the first three images) is from a Roman villa, second century BCE, and is signed “Heraclitus” at the bottom near the theatrical masks…

The Medieval Portrait

In the Early Renaissance, portraits had a commemorative function. With the exception of devotional images—Christ, the Virgin, and saints on altarpieces, shown front-facing—portraits were in profile and no less canonical.

The model for such portraits came from antiquity: Roman coins, medals, and reliefs with imperial heads. The aim was triumph and glorification, which called for generalization and typification rather than strict truthfulness or realism. The medieval portrait preserved memory and exalted the great.

Leonardo da Vinci broke with this tradition in the very early 16th century with the Mona Lisa. The portrait’s new task became a dialogue that dissolves Quattrocento iconography, stasis, and stiffness. Mona Lisa is half-length, turned toward us in a three-quarter view, with a slight turn of the head, the hands set before her, space unfolding around the sitter, a psychological landscape, and a unified color world. The smile becomes an end in itself, and psychology emerges without imposed religious or ethical directives. Before the Mona Lisa, Leonardo painted the Lady with an Ermine, also three-quarter and with the hands visible, but she looks to the side and belongs to an earlier phase…

Colosseum and the Funerary Cult

The Colosseum was built in the first century CE under Emperor Vespasian, on the site of Nero’s Golden House, partly to wipe away the memory of the previous ruler. One of its main attractions was the gladiatorial games.

The first recorded fights took place in the third century BCE, when the sons of an aristocratic politician staged gladiator combats at their father’s funeral to honor him. This form of paying tribute to the dead grew out of a funerary cult that the Romans adopted from the Etruscans.

The Etruscans were a highly developed civilization, contemporaries of ancient Greece. They lived in what is now central and northern Italy, Tuscany today and Etruria then, during the first millennium BCE.

One rite of the funerary cult involved “games” held at the graveside. Homeric-age Greeks also had funeral games with a martial character. In Rome these contests first moved into the circus, which was closer to a racetrack than to a modern circus, and later evolved into the bloody gladiatorial shows that became one of the most popular public spectacles at the Colosseum. By the imperial period the commemorative meaning had faded, and the bouts were instead tied to religious festivals…

The Abduction of Europa

This theme entered art from ancient Greek mythology, where Europa, daughter of a Phoenician king, is abducted by Zeus, the chief Olympian god, who appears in the form of a bull.

The image repeats itself across the centuries and rivals the popularity of many biblical subjects, even though those are far younger than the legend of Europa’s abduction.

I have chosen several works from world art, from the earliest I have encountered to one of the most famous later pieces, so you can see how artists reinterpreted this story from century to century.

Where It All Began

I often feel like I’ve been doing this forever, and you can choose different points as the “start.”

It could be when I was seven and entered art school.

Or when, at thirteen, I stopped copying and started making my own illustrations.

Or when I first studied industrial design, then later studied web design and contemporary art.

Or maybe it began each time I returned to design and then stepped away, discovering the same thing: my strength and sincerity live where I notice beauty—and try to translate it through my skills in illustration and painting.